Winter

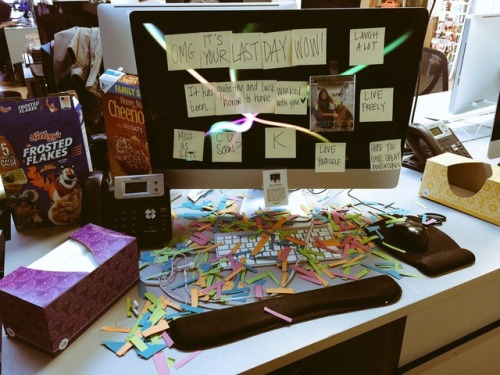

It was our first New Year’s Eve without my father. I dipped strawberries in melted chocolate and watched my mother stir rice pudding. The family was coming over to our house. Despite the brutal absence, we were supposed to be celebrating. My brother, George, got engaged. I have big life news as well, I told everyone. I am quitting my job.

Family members congratulated my brother while raising their eyebrows at me. They didn’t hide their distaste when they told me I needed to reassess my life choices. They told me to wait until I found a new job first—to not be totally broke. I told them I was already broke. I told them my last Uber driver disclosed his salary to me. It was unprompted, and I wished I didn’t hear it because when I told him my salary in the same trusting nature, he asked me if my wage was even legal. On the bright side, I said, my free time will be spent searching for a husband full time. They are traditionalists who couldn’t believe I was not married with children already.

Around the same time, I was reading Zoey Leigh Peterson’s Next Year For Sure, which offered a dual perspective into a progressive relationship. Kathryn and Chris were dating for nearly a decade when Chris began to have feelings for another woman, Emily. The first chapter began with Chris admitting his crush to Emily.

This confession was not out of the ordinary for them. They had an open and honest relationship, divulging all their stories and secrets to each other. The news of Chris’ crush sent Kathryn into a flurry of wild emotions that she hid with nonchalance. Despite her instinct to shut down the idea, she encouraged Chris to date Emily. Their stable relationship of finishing each other’s sentences and nightly, weekly, and yearly routines unraveled. They knew everything about each other, including memories from before they got together. One night, Chris told Emily a new detail to the story Kathryn had heard hundreds of times; this simple act of Emily tapping into unfamiliar territory of Chris’ astonished and confused Kathryn.

I felt equally betrayed reading that. How could Chris do that to Kathryn? What was so special about Emily that he couldn’t just appreciate her as a friend? What was Kathryn thinking supporting Chris’ decision to date her and another girl at once when it made her uncomfortable? I started to reflect on all the relationships in my life, all the people who have come and gone. I didn’t know what made a person irreplaceable. I didn’t know how to trust anyone to stick around. Chris was happy with and faithful to Kathryn for a long time before he met Emily at a laundromat. A simple interaction and his feelings changed, a momentary thrill that he wanted to chase.

My dad was the person who made me happy when I was sad without trying, without knowing I was sad. Just seeing him would brighten my day. I hadn’t met anyone who’s absence I would care more about than my father’s. I didn’t give people the chance, but I saw no point.

So, I did not search for a husband in my free time, as promised. I instead focused on getting a new job. By the end of the season, I accepted and began a new marketing gig.

Spring

I was crying very often. And not because of my grief, but because of my job. The learning curve was rough and I was consumed by work. I went into the office early, left late, then went to sleep and dreamt about work. No matter how focused I was, my role was still challenging.

To make matters worse, I had no friends. My only companions were my boss and the Spotify Discover Weekly playlists. One day I forgot my headphones at home. Around noon, the group of people around me all began coordinating lunch plans, during which I sat with my eyes glued to the computer screen, pretending I couldn’t hear them making plans without me.

It felt bizarre spending eight hours a day being surrounded by people in an open floor plan, but feeling utterly alone. I didn’t even have a cubicle to blame. In Jeffrey Toobin’s American Heiress, Patty Hearst’s life before being kidnapped by the SLA (Symbionese Liberation Army) appeared fulfilled. She was engaged to and living with her math tutor, Steve Weed, who was six years her senior. It was a banal relationship she thought might be more exciting by moving in together and getting engaged. This was not the case. Toobin wrote:

Patricia cooked and cleaned; Steve did neither. They did everything, including have sex, on his schedule, not hers. Patricia made the beds or left them unmade, as she did on February 4. Their evening together on that occasion was typical. Dinner was chicken soup with tuna fish sandwiches, followed by Mission: Impossible on television, then schoolwork in silence on the downstairs sofa. Bathrobe and slippers had become her home uniform. At nineteen, this was her life? On the eve of her kidnapping, Patricia later acknowledged, she was "mildly suicidal."

I, too, felt shackled to a routine I did not want for myself: wake up, work, go home, work, sleep, and repeat. There was a lot to do and a lot more to learn. I no longer felt the rush of an idea for a new passion project in my spare time. It took me twice as long to read books. I stopped making plans on weeknights because I didn’t want to commit to anything that might force me to leave the office before my work was finished. On nights that I left the office early, I would stop by a neighboring bookstore and browse the shelves or listen to a guest speaker, feeling too tired to be inspired. Patty was trapped in an engagement; I was trapped in Outlook.

At 25, this was my life?

I pretended that not being invited to a lunch out with coworkers was what hurt, but really, I was feeling isolated from the people most important to me, my friends and family, and it wasn’t because of my headphones.

Summer

The weather was beautiful, and I was again reminded of the ugliness in this season. I braced myself for the one year anniversary of my father's death: July 14. He passed away on a Thursday; this year, it fell on a Friday. I stayed home from work and my family visited his grave together. The next day, we had a mass at church for him. I was sitting at the altar, reminded of everything I lost, when I saw four friends walk inside. They stood in the back, not understanding the Arabic prayers or Coptic writing. I joined them, and couldn’t help laughing at the sight of them. They traveled an hour out of their way, back and forth. I felt inappropriate for laughing, until I stood with my mom and watched her have the same reaction to her friend, a stranger to our religion, entering mass to stand by her side.

The following week, George, my mom, and I traveled to Egypt. I was too busy to pack my bags because of work, so my mom did. My suitcase was vibrant. It’s time to for a change, she told me. No more black clothing. I obeyed, but not without guiltily pointing out the hypocrisy in her black clothing. It’s different, she told me calmly.

It was our first time back in years. My father and I were supposed to visit Egypt the year before; our trip was scheduled for a month after his passing. Being there without my dad felt wrong. Egypt was his home. When my grandparents moved the family to America, my father was the only one left behind. He refused to leave, instead choosing to crash with his aunt and cousin. It took two years for them to finally force him onto a plane to the States. After he moved, he went back to Egypt every year, sometimes twice a year.

He always said he wanted to retire in Egypt by the Red Sea. I loved Egypt, too. I spent almost every summer of my life in Egypt, always beginning the fall school year much chunkier because of my many helpings of its delicious, high-caloric food. The loud streets of Cairo echoed my father’s presence in every corner. I associated everything, from the dusty air to the sun’s enveloping blaze, with him. Egypt was still his home.

In Maria Semple’s Where’d You Go, Bernadette, the character Bernadette barely left her home. She found solace in it, despite its incomplete renovation. When her daughter asked to go on a family trip to Antarctica as a reward for good grades, Bernadette hesitantly agreed. She had (what I would diagnose as) mild agoraphobia. In an effort to prepare, she contacted her virtual assistant for the strongest medicine for seasickness (“stronger than Dramamine”), among other excessive requests. The highlighted theatrics behind her anxiety makes it easy for readers to gloss over the sacrificial nature of Bernadette. She felt true conflict in leaving her comfort zone, and although she plots ways to back out of the trip, she ultimately planned to go on the trip for her daughter.

Our trip to Egypt was difficult for me, but for my mother it was a repeating stab to the heart. She was surrounded by her entire family in her home country. She should have been happy, but she couldn’t fully be. She never spoke too much about her feelings. She would cry a little some days. Other times, she’d talk about my father to elicit reminiscence from people. Most of the time, she seemed to enjoy the moments without mentioning him.

One night, we were sitting outside, the only noise the sound of the can of OFF! being passed around. To no one in particular, maybe to the sky, she said, I miss him.

I remembered in that moment something that keeps me up at night. My mom had been living outside of her comfort zone for a year. I didn't want to wonder if that would ever change.

Fall

Now it was time for my oldest brother, Joe, to make an announcement: he was moving. To Cyprus. In two weeks. He’d quit his job and was moving back home for the two weeks in between. I stayed with him and enjoyed the short time I got to live under the same roof with my brothers, possibly for the last time ever. Growing up in a tight-knit family (my cousins lived right next door for most of my life), no one took this news lightly. The idea of me moving a train ride away from New Jersey was already a world away in their minds. Moving across the globe to a foreign country no one had ever visited was staggering.

This return to our childhoods felt very ordinary, otherwise. My brothers and I fell into our old routines of racing to use the bathroom in the morning and spending far too long trying to agree on a movie to watch. Before I knew it, I was waking up to hug and kiss my brother goodbye and safe travels. I kept pestering him for a return date, foolishly asking if he’d try to come back for Christmas. Christmas was a month away, and although it made no sense for him to return in that time, I could not comprehend celebrating the holiday without him.

It was beginning to be the holiday season, and I was glum. There was a time in my life when this time of the year was my favorite. I loved shopping for my family and friends, excited by a holiday that promoted gift giving.

This year, I asked my family if we could skip the gifts and tree. All I saw in Christmas trees was the mess that would be left to clean in January. George was insistent on a tree. My mother compromised by setting a miniature tree in the family room.

While everyone around me expressed gratitude for all they had, I felt burdened by all I’d lost. My favorite thing about life--my family--had dwindled from five to three. My boisterous tight-knit extended family that I saw multiple times a month rarely got together anymore.

I read André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name next to my dog by my family’s fireplace. A comforting surrounding for a heart-wrenching story. It took place in Italy, sometime in the 1980s, and was written from the perspective of 17-year-old Elio. Elio was attracted to his family’s summer guest, Oliver, and experienced a full body and mental torment as he idolized Oliver from across the backyard. He compared the feeling to fire: “Not a fire of passion, not a ravaging fire, but something paralyzing, like the fire of cluster bombs that suck up the oxygen around them and leave you panting because you’ve been kicked in the gut and a vacuum has ripped up every living lung issue and dried your mouth, and you hope nobody speaks, because you can’t talk, and you pray no one asks you to move, because your heart is clogged and beats so fast it would sooner spit out shards of glass than let anything else flow through its narrowed chambers.”

The two spent their afternoons together and came together in a triumphant, intense bond. Their passion lasted what felt like seconds, but was actually a few weeks, before Oliver had to return back to the States.

When Oliver visited a few months later, he was engaged to someone else. Years passed. Oliver got married, had kids. Elio was successful in an unspecified field; he got involved with people he identified as “those after Oliver.” Their few reunions were outwardly platonic and mostly reminiscent. Their actions were restricted, but Elio’s, and I’d like to believe Oliver’s, feelings of longing from so long ago were unchanged.

The notion that feelings live on, with the capacity to bring back a few weeks of one summer, scared me. It was years later and Elio still subconsciously craved Oliver’s touch. He would never fully get over him. Time didn’t actually heal all.

A few months after my dad passed away, a friend told me he wished I could go back to normal, to the old Nat he loved. I should have been mad at him, but instead I felt awful. I felt awful because it occurred to me that I would never be the same, that I lost the person I once was. Until this, I experienced nothing substantial to be sad about. Sure, I found things: bad grades, boys, the movie My Dog Skip. Never anything tangible. An old coworker once told me I didn’t walk, I skipped. It was true. I was free of pain.

I’ll never have that freedom back. I identify as someone who’s lost a parent. Suddenly. So, so sadly. And that’s a narrative that I’m not sure I’ll ever escape.

I expect more pain will come. Like Elio and Oliver, I will experience a full life, find love elsewhere, etc. But these feelings of grief will always be there. My father was my best friend, and if mourning him is the consequence of loving him, then my heart will forever dress in black.

Natalia is an editor of Things Created By People. Find more of her work on her website.